Concerns about "screen time" are nothing new. For decades, we were worried that people were watching too much TV. Now, the conversation has shifted to mobile phones.

At the surface level, this seems like a pretty standard evolution. TVs, computers, tablets, phones... these are all just screens, right? In the same way that we measured and limited the time we spent watching TV, can't we simply measure and limit the time we spend on our phones?

In the past few months, all the biggest mobile platforms and apps have introduced tools to track time spent. But I think we'll need a more nuanced approach to how we design for "screen time" as technologists, and how we talk about these ideas as a society.

This time, it's different

We're only a few years into the era where the majority of humans have a supercomputer in their pocket which is connected to every other supercomputer in every other pocket. There are two important factors that intersect to make this moment different.

First — "Looking at a screen" isn't really the activity we're taking part in anymore. A mobile screen, at least in theory, is a window into a much wider range of potential experiences than a TV screen. With your phone, you can talk to friends, find someone to date, read a book, play a game, make money, or watch a video. Compare this with the TV in your living room: you can watch the news, watch sports, or watch a sitcom... but no matter what, the activity you're taking part in is still watching TV in your living room.

Second — and more importantly — mobile phones can occupy the idle moments throughout your day in a way that TVs and computers cannot. It's hard to overstate how wild this is. Ten years ago, if you were waiting in line or sitting in a taxi, your activity would have been waiting in line or sitting in a taxi. Now your activity can be anything! The hours we're racking up on phones are mostly distributed across many short sessions throughout the day. This is in sharp contrast to the dark ages when we needed to carve out a block of leisure time in order to watch TV or use the computer.

Sessions, activities, and outcomes

What does this mean for how we design for and talk about screen time?

As a starting point, we should stop thinking about this as a "time spent" problem where the solution is simply counting the time we spend on different apps. The era of online and offline as binary states is over and the distinction will get even murkier with augmented and mixed reality. We exist fluidly between physical and digital spaces, and there's no going back. The language we use is important, and blunt language will lead us towards blunt solutions for a very nuanced and important problem.

No, the devil does not live in our phones, and hordes of Silicon Valley executives won't be tossing their kids' iPads off the Golden Gate Bridge any time soon. Instead of talking about screen time per se, we should start talking more about sessions, activities, and outcomes.

We should treat it as a given that (a) many times a day, people will find themselves with a few moments of idle time, and (b) they will usually turn to a digital space in these moments — and that's okay!

The most successful mobile apps of the future will facilitate some activity to convert the idle moments throughout your day into positive outcomes. And they will be explicitly designed for short sessions, which better map to the natural rhythm of our lives.

Mobile phones and "found" time

Most people only have a few blocks of leisure time a week, if they're lucky, that can be dedicated to something like watching a sixty minute TV show.

The first digital experiences (movies, TV, video games) were all designed for long sessions that took place in front of a TV or a computer. Reed Hastings (the CEO of Netflix) has famously and accurately claimed that their biggest competitor is sleep, not Youtube or Facebook.

When mobile phones unlocked idle gaps for the first time, the first wave of successful apps (social feeds, casual games, and dating) all had one thing in common. They were flexibly designed for sessions of any length. Feeds of short form content and swipeable cards are the perfect elastic containers. You can scroll through five things or five hundred things; the container doesn't care.

It always takes time and iteration before we fully realize the unique potential of a new medium. The first television ad — a voiceover paired with a static image — is my favorite example:

On mobile, feeds were a great start! But the true potential of mobile as a medium might lie in helping us fill the idle gaps in our day with a better activity than the default alternatives. And then encouraging us to continue on with our day.

Instead of settling for apps that can flexibly accommodate short and long sessions, we need more apps that are explicitly designed for short sessions.

Outside of utilities like the calculator, weather, and on-demand services, almost no apps are explicitly designed to help you accomplish some goal and then leave.

Neko Atsume is a cult-hit Japanese game where the only gameplay is arranging objects in a garden to attract gift-bearing cats. But the cats will only visit while the app is closed, and you only know of their visits because of the gifts they left behind. After using the app for thirty seconds, you run out of things to do. And the longer you wait until your next session, the better it gets. It's the only example of these design patterns that I could find. It's incredibly boring, and it's amazing. It's a guaranteed way to convert thirty seconds into a warm and fuzzy feeling.

It's curious that more apps don't explicitly design for short sessions. Business models obviously play a role, and enough has been discussed about the relative merits and downsides of ad-support models that I won't re-hash them here. Instead, I'll outline three ideas for how to think about designing mobile apps for the future.

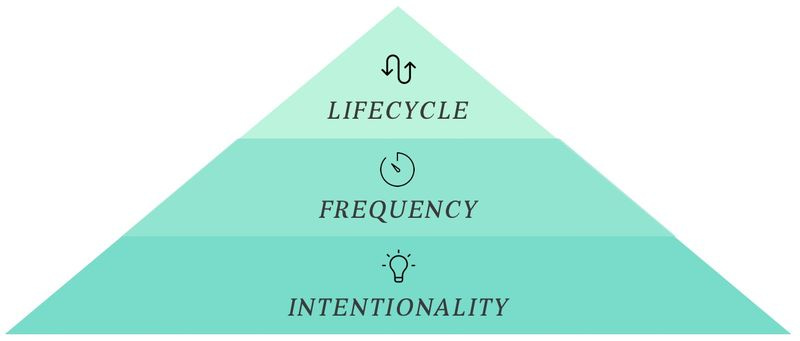

1 — Intentionality

It sounds obvious that every app should have a clearly stated purpose, but in reality many apps converge to the same outcome: entertainment. Imagine an experiment where two questions were asked every time someone puts a phone back into their pocket: (1) what were you up to just now, and (2) what was the outcome? The most common answers would be: "scrolling through some content" and "mildly entertained."

As a directory of two billion people, Facebook can offer up some pretty amazing outcomes: finding a job, finding a date, buying and selling stuff, participating in a global conversation around a topic. Facebook now optimizes for "meaningful social interactions" instead of time spent. It's something that Facebook can uniquely facilitate, and it's encouraging to see it as an explicitly stated goal.

One way to make sure that user behavior directly maps to a positive outcome is to ask your users to pay for that outcome. This has always worked well for utility apps and is starting to work for a wider range of verticals too, like meditation and fitness. On iOS alone, there are more than 300M paid subscriptions across 30k apps, growing at 60% a year.

2 — Frequency

Based on the stated purpose of the app, how often should it be used? For example, an app that curates the top ten news headlines every day would be naturally used around once a day if successful.

Most apps probably don't need to be opened up a dozen times times a day, and thirsty push notifications that try to get users back in will increasingly backfire as people become more self-aware of how they use their phones.

Understanding the expected frequency pattern is also a great way to correctly measure an app's growth and product/market fit. If your app could successfully deliver its stated value when used around once a week, then measuring active users and retention on a weekly basis will be more helpful than a daily or monthly time window.

3 — Lifecycle of a session

This is the most important concept for a modern mobile app developer to internalize.

The right way to think about "time spent" is not to limit the overall amount of time spent inside an app, but to carefully determine how time translates to value over the course of a single session. The value per unit of time within a session is almost never consistent! It follows a pattern and that pattern is completely set by design decisions within your control.

Let's examine a utility app, like Uber. You open up Uber with a clear goal in mind: to summon a car that can take you from point A to point B. Entering your address, comparing rates, and picking a payment method — these activities don't provide any value in and of themselves, they are just preamble to seeing that "Jason, 4.94 stars is 3 minutes away."

The lifecycle of value per unit time for an app like Uber follows a step function:

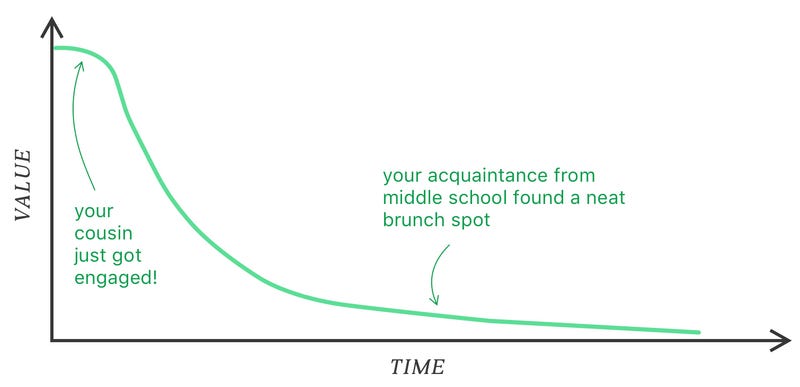

Apps centered around content or interactions are more complicated. Infinite feeds that are algorithmically ranked by relevance will be great at the beginning of a session, then get less interesting over time — by definition. The value lifecycle curve of Facebook or Instagram might look something like this:

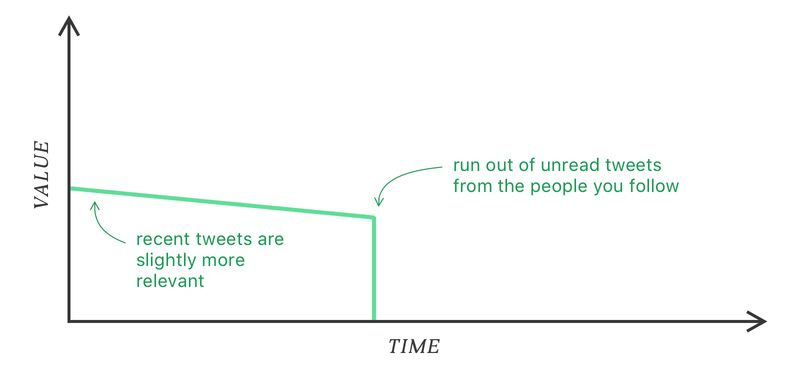

A finite pool of content displayed in reverse-chronological order will have less steep of a decay, but probably won't start on as high of a note. Twitter's value lifecycle might look like this:

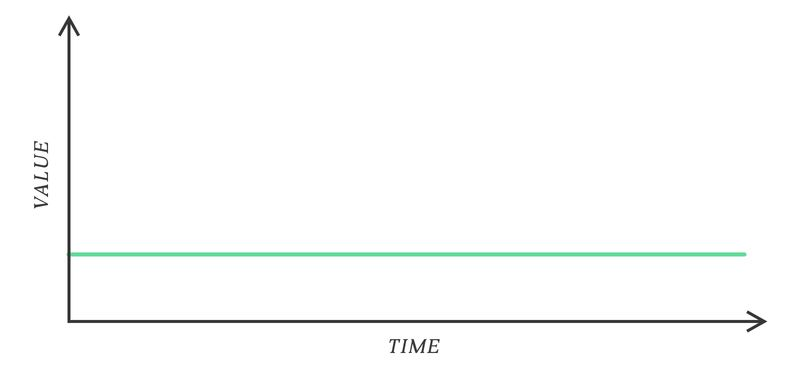

And just for fun, let's look at the theoretical value lifecycle of reading a book. It probably looks something like this:

The fact that ranked feeds outperform chronological feeds is about as concrete a rule as any in social software. This is why Facebook's News Feed has always held steady with "top" VS "most recent", why Instagram switched over to a ranked feed, and why Twitter has even started embedding ranked sections inside their stream.

Despite consistent public requests for a chronological feed on Facebook, any experiment to flip the default results in less time spent on News Feed and less overall engagement. It seems like a conundrum where what people say they want and how they empirically act are out of sync.

But visualizing these lifecycle value curves offers up an explanation.

How you feel about an app session is not only based on the "area under the curve", so to speak. Your feelings are also influenced by the highs and lows. You will always exit a ranked feed at the lowest point on your value curve, by definition. And if you check an app frequently (the encouraged behavior amongst social apps), your starting point gets lower as there's less relevant inventory for the feed to draw upon.

It’s about to get weird

Reasons behind the collective malaise we feel around screens and social media can't just come down to the idea that we’re simply spending too much time on screens.

A more useful framing needs to start with the fact that we suddenly have a new superpower we can wield during the idle moments that have always existed in our lives, and the acknowledgement that being mildly entertained is usually a better outcome than doing nothing at all. From there, we can think creatively about how to translate these idle moments into a wider range of interesting outcomes.

I'm excited for apps that get better as you use them less frequently. Apps with "business hours" that are closed most of the time, but magical when open. Social and content-based apps that help you accomplish a "task" and then kick you out. Apps that are primarily about participation instead of consumption. Apps that people will happily pay for because they're the most important space — digital or physical — that they could hope to occupy.

These ideas sound like the exact opposite of what has made consumer apps successful for the past decade. But I think we're just starting to scratch the surface on one of the biggest opportunities that mobile can offer: unlocking the idle moments (found time!) in our day.

And when we figure this out, we'll have solved the "screen time" problem too.

Having just read, ‘Why do we work?’ I find it interesting that ‘idle time’ is something we need to solve for, because it suggests we have a misplaced value in ‘productivity’. What if those few moments waiting in line are an opportunity to connect with a neighbor, or that brief moment of pause on the couch in the morning is a chance to snuggle with your toddler.

Substack has introduced me to many interesting/insightful voices that I can engage with in those moments of ‘downtime’, and I am already finding that it is one more thing that can take me away from those that probably need me to be most present to them.

thanks for sharing this, Sachin 🙏🏼

i wonder how/if your thoughts have changed since 2018.

i'd also like to put my recent post (re: digital heroin) on your radar. https://opentochange.substack.com/p/growing-up-before-digital-heroin